News Center

Explore expert insights, practical guides, and the latest news on SolaX Power.

-

Award Highlights

-

Exhibitions Review

-

Corporate Updates

-

News

June 18, 2025

SolaX Power Honored with 2025 -

News

June 12, 2025

SolaX Power Secures Dual AA+ Rating for Inverters and Storage from EUPD Research -

News

June 10, 2025

SolaX Power Showcases Brand Strength with Triple PVBL Honors -

News

June 12, 2025

SolaX Power Honors Energy of Love at SNEC for Outstanding Community Contributions -

News

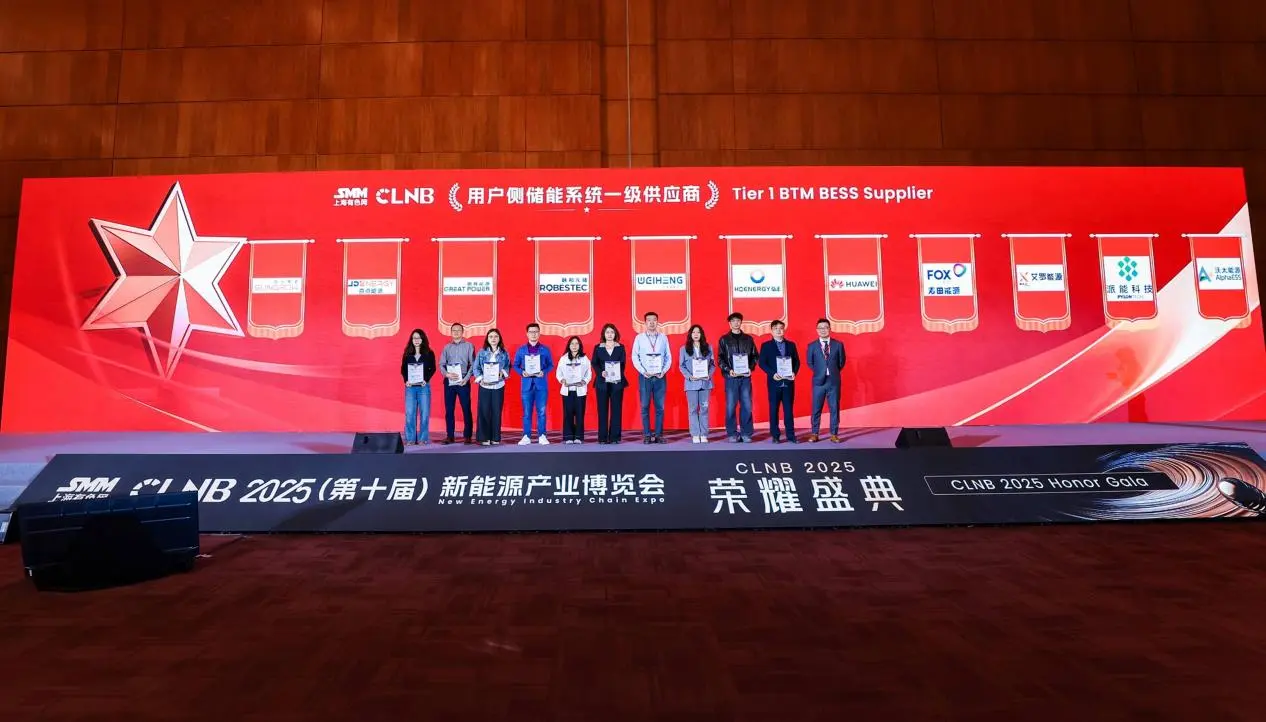

April 18, 2025

SolaX Ranked SMM Global Tier 1 BTM BESS Supplier: A Major Milestone in Energy Storage -

News

March 05, 2025

SolaX Power Named Top 10 Inverter Brands at the 8th Distributed Solar Summit China -

News

February 28, 2025

SolaX Power Secures “Top Brand PV USA 2025” Award, Reinforcing Its Leadership in the Rapidly Growing U.S. Solar Market -

News

December 16, 2024

Awards Highlights | SolaX Wins 2024 GGll Golden Globe Award for“Innovative Product of the Year” -

News

November 26, 2024

Award Highlights | SolaX Power Achieves TÜV Rheinland VDE 4110 & 4120 Certification for X3-MEGA G2 Inverter

To the Latest Newsletter

Stay Ahead with the Latest SolaX Updates!

Sign up

I have read and agree to Privacy Policy and User Terms